Biomass in the Renewable Energy Directive: all smoke and no fire?

Article by Erica Gentili, Junior Communications Officer for BirdLife Europe

In March 2023, European leaders reached an agreement on new limits for the use of forest biomass under the EU’s Renewable Energy Directive (RED). The agreed version of the law was made official following the adoption by the European Parliament and the Council. This policy aims to eliminate subsidies for energy generated by burning certain categories of forest wood, and disqualify burning wood from primary and old-growth forests from counting toward renewable energy targets. However, the agreement contains numerous loopholes and derogations that will allow business as usual on the ground.

The European Parliament’s proposal to reduce the amount of energy from forest biomass that counts toward renewable energy targets was rejected by the Council. This means that EU countries now have the flexibility to add new requirements governing what kind of biomass qualifies as renewable energy, leaving room for means of escape.

While we can consider the inclusion of new requirements linking biomass to the loss of forest carbon sinks and the prioritization of long-lived uses of wood as a win, many NGOs have condemned the agreement for its failure to reduce the amount of wood burning considered “renewable” energy. The enforcement of these requirements will ultimately depend on Member States adopting stronger restrictions for the use of forest wood for fuel.

These are the main elements included in the agreement:

Limits on the amount and kinds of forest biomass receiving subsidies

The agreement includes limits on the kinds of forest biomass eligible for subsidies. Certain categories of wood, such as saw logs and veneer logs, industrial-grade roundwood, stumps, and roots, are excluded from direct financial support. However, the impact of these limits is uncertain as Member States have free reign on determining what wood qualifies as “industrial grade roundwood.” Additionally, the definition of “industrial grade roundwood” does not prevent the burning of whole trees that do not fall into these categories.

Cascading principle

The introduction of the cascading principle, which prioritizes the highest economic and environmental added value of woody biomass, is another feature of the agreement. However, Member States can derogate from this principle for reasons such as ensuring energy security or when the local industry is unable to use forest biomass. In other words, they can simply dodge this requirement.

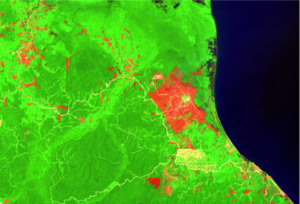

Disqualification of wood from old-growth forests and other special ecosystems

The agreement disqualifies wood sourced from old-growth forests and other special ecosystems from counting toward renewable energy targets or receiving subsidies, but Member States still have significant leeway in defining these ecosystems. This creates a major loophole, as weak definitions in countries like Sweden and Romania would allow old-growth forests to be harvested.

New sustainability criteria

Member States will be allowed to adopt new sustainability criteria for biomass fuels, and the agreement includes provisions to ensure that biomass use does not undermine land carbon sinks. This was a win for NGOs, as most Member States will only achieve targets if forests are protected and restored. The Restoration and Deforestation Law could play a bigger role on forest biomass. Additional limits apply to biomass electricity, with disqualifications for certain power plants, but derogations for plants in “just transition” regions, those employing biomass CO2 capture and storage, and plants that have already received support.

Biofuels

Regarding biofuels, the agreement maintains the cap on crop-based biofuels at 2020 levels, but their use remains optional for Member States. The Commission will review the use of high deforestation-risk biofuels this year, and there is potential for accelerating the removal of palm biofuels from EU renewable energy targets. A sub-target of 5.5% for advanced biofuels and RFNBOs (Renewable Fuels of Non-Biological Origin) has been agreed upon, with a 1% binding target for RFNBOs.

Marilda Dhaskali, Agriculture and Bioenergy Policy Officer at BirdLife Europe, commented on the file: “Once again, energy ministers and the EU Parliament have ignored science and have shown how little they care for the wellbeing of people. While droughts, floods, and wildfires are ever-increasing, nature should be our first ally to fight back. Yet, our leaders continue to make decisions that cause the acceleration of the climate and nature crises. It angers me that, again, profit was put first, and that people continue to use the intentionally spread lie that burning wood and food for energy is carbon neutral.”

Another defeat was the missing requirements of doing environmental impact assessment in renewable acceleration areas (also known as go-to areas), that were removed from the directive. This is a missed chance to accelerate wind and solar development through sound spatial planning and increasing administrative capacities in Member States.

Carla Freund, Policy Officer for Nature-friendly Energy Transition in Europe at NABU, added: “Environmental impact assessments are essential to ensure that the energy transition is harmonious with nature and people. Instead of speeding up development, these new rules can actually end up slowing down progress towards achieving our renewable energy targets.”

Overall, while the agreement contains some positive developments, such as limits on certain types of forest biomass and requirements for compatibility with land carbon sink targets, the numerous loopholes and weak definitions raise concerns about the effectiveness of the policy. Stronger restrictions and enforcement at the Member State level will be crucial to ensure the sustainable use of forest biomass.