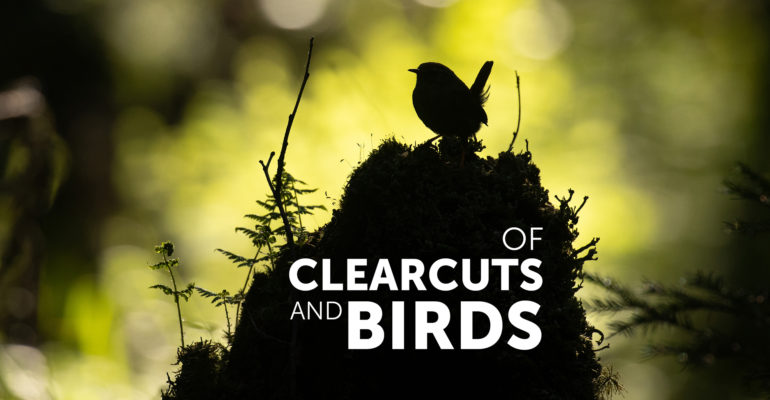

OF CLEARCUTS & BIRDS #1

How bioenergy increases the pressure on forests

Through the voices of our local Partners, our series “of clearcuts and birds” tells some of the stories of Finnish, Estonian and Latvian forests and of their incredible biodiversity, as well as the hard consequences of their exploitations, (in)directly driven by the EU’s support for bioenergy.

Forests are sacred to many, and in many ways. They are home to incredible fauna and flora. They provide us with food, material, inspiration and peace. Old forests have been around for centuries. They are full of stories they want to share, if you will listen. And despite being betrayed by human exploitation, and fires, they grow back, again and again, if we let them.

But the rate of human activities in the 21st century does not respect the time of forests. If we don’t look closely, forests will be silenced for good.

Through the voices of our local Partners, our series “of clearcuts and birds” tells some of the stories of Finnish, Estonian and Latvian forests and of their incredible biodiversity, as well as the hard consequences of their exploitations, (in)directly driven by the EU’s support for bioenergy.

THE STATE OF FORESTS IN EUROPE

In general, it is difficult to provide a proper overview of the state of forests in the EU, because forestry policy is primarily a national competence. The collection of data might differ from a country to another, and the issues are not the same in different locations. However, many EU policy instruments for biodiversity and climate change have an effect on forests, like the Birds and Habitats Directives which provides tools for their protection.

In 2018, the EU27 land surface was covered by 158 million hectares of forests, which represents 39% of its total land area. Only a few primary forests remain since human activities affect more than 95 % of EU forests. 36 million hectares of forest area are part of the Natura 2000 protection network. Unfortunately, it is not an absolute protection as some of these forests are still facing clearcuts.

The 2020 State of Europe’s Forests report determines that the condition of European forests is on average deteriorating. Looking at the European Environment Agency report ‘State of nature in the EU 2013-2018’, which is based on areas protected under the EU Birds and Habitats Directives, 85% of protected forests in the EU are in poor or bad condition, 54% and 31% respectively. The worst scenarios can be expected for unprotected or less protected areas which depend on national law or on the good will of private forest owners.

Forests host nearly 90 % of the world’s terrestrial biodiversity. It should be a duty to take care of them. Biodiversity is richer in older forests, as they have a more significant volume of deadwood and greater structural complexity of trees and plants of different ages. 20 to 40% of forests species require the presence of decaying wood at a stage of their life cycle.

BIOENERGY OR THE HUNGER FOR WOOD

Bioenergy is energy produced by burning fuels made from organic materials, such as wood, agricultural crops, or organic waste. At the EU level, 60% of bioenergy is produced by burning wood. In 2018, almost half of the woody biomass used in the EU was consumed as energy. Bioenergy production significantly affects forests.

The Renewable Energy Directive (RED) is a key feature of EU climate policy aiming to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by stimulating the consumption of energy from renewable sources. Energy sources promoted by the RED are being subsidised with billions of euros by EU countries as an alternative to fossil fuels and a solution to tackle climate change.

But the crux of bioenergy is: burning wood emits CO2. By cutting down our forests to burn them for energy, we release CO2 in the atmosphere, accelerating the climate crisis. Even if new trees can regrow and reabsorb the emissions, it takes time. Time that we do not have. “Replacing” forests takes decades, even centuries, depending on the age of the burnt trees. Meanwhile, the emitted CO2 continues to increase global warming. From a climate perspective, we are literally burning our carbon sinks.

At least 37% (and up to 51%) of the wood used for bioenergy in the EU is sourced directly from forests. It is called “primary woody biomass”. Clearcutting is a compatible practice with bioenergy. The “best” trees will be used for materials or as pulpwood, and the rest will go to energy production. But while this burnt wood is considered to be of low economic value, it can play a major role for forest biodiversity as dead wood or… living forest. The investigative report of Forest Defender Alliance shows that large tree trunks are also used to produce tiny wood pellets and energy.

If any more proof was needed, the Global Forest Watch’s map shows the forest cover loss since 2010. While trees do regrow and might compensate (a fraction of) the loss of growth forests, the ever-increasing pressure our remaining forests face are huge.

Tree cover loss by more than 50% of canopy density from 2010 to 2021. Loss of tree cover may occur for many reasons, including deforestation, fire, and logging within the course of sustainable forestry operations. In sustainably managed forests, the “loss” will eventually show up as “gain, as young trees get large enough to achieve canopy closure.

A JOURNEY TO FINNISH, ESTONIAN AND LATVIAN FORESTS

While bioenergy subsidies and incentives are decided at EU-level, their consequences in the field are tangible. Each country situation is different and faces their own issues, but the hunger for wood is common.

Karl Adami is an Estonian photographer who has dedicated his work to forests and birds. He published two books about forests and is collaborating on the Estonian television’s nature show ‘Osoon’ for the past ten years. “The more you know, the more you care”, says Karl, “The more you realize how fragile or demanding some species are and how much time is necessary for them to have a suitable environment, the more you become protective of old-growth forests.”

Karl is worried about the situation in Estonia: “In the past six years, the logging has increased significantly. What irritates me the most is probably the constant downgrading of deadwood. The mainstream narrative is that deadwood, both standing and fallen, would just rot if not removed from forest. But thousands of species are linked to dead wood. For some forest birds it is a source of food or provides the ideal site for nesting.”

For BirdLife, Karl travelled through Finland, Estonia, and Latvia to take pictures of forests and clearcut areas that can be found all around the countries. Our national Partners help us understand each local situation.

A series of articles by Julien Bacus. Pictures by Karl Adami .

A huge thanks to Karl Adami, Teemu Lehtiniemi, Tero Toivanen, Marko Halonen, Hanna Aho, Juha Aromaa, Kaarel Võhandu, Siim Kuresoo, Liina Steinberg, Indrek Tammekänd, Viesturs Kerus, Jānis Ķuze, Pierre-Jean Sol Brasier, Kelsey Perlman, Kenneth Richter, Juliette Scarato, Anna Staneva, Caroline Herman and Honey Kohan for their testimonies and their precious help during the edition of this series.

FINLAND

ESTONIA