Biodiesel: a cure worse than the fossil disease

By Lisa Benedetti, BirdLife Europe

Biodiesel is the most consumed biofuel in Europe. It is projected to make up almost 70% of the EU biofuels market by 2020. This dependence poses some questions, so the European Commission is now considering what its energy policy for transport should be for 2020-2030, especially what role such biofuels should play. Sustainable transport group Transport & Environment (T&E) has stepped in and taken a close look at the numbers. It found that the extra emissions from biodiesel – considering a full life-cycle approach – would be equal to putting about 12 million additional cars on Europe’s roads in 2020.

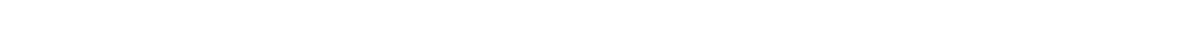

The European Commission’s communication on a 2030 framework for climate and energy says that ‘food-based biofuels should not receive public support after 2020.’ This is a solid policy principle because the emissions from these fuels are actually much higher than those arising from fossil fuels, and especially those from advanced biofuels (for example, perennials and short-rotation coppice like switchgrass and willow). On average, first-generation food-based biofuels have 50% higher lifecycle GHG emissions than fossil equivalents so phasing them out would reduce transport emissions significantly.

Although the EU set a limit on land-based biofuels this reform doesn’t include ILUC emissions in the carbon accounting of biofuels under the Renewable Energy Directive (RED) and Fuel Quality Directive. This means that harmful biofuels can still be counted toward EU targets and receive public financial support. Under some pressure to address this, the European Commission studied the biofuels issue again and released the so-called Globiom report. This study considers land-use change (LUC) emissions resulting from additional demand for biofuels and does not assess their overall impact compared to fossil fuels.

T&E has undertaken a much deeper analysis to provide a clearer picture of what is going on. What they found is that instead of reducing CO2 emissions, using biodiesel for transport could increase Europe’s overall transport emissions by almost 4%. These extra emissions are equivalent to putting about 12 million additional cars on Europe’s roads in 2020. It’s a lot more than the emissions saved from all lorry road charging systems in Europe, for instance.

This long delayed EU study found palm, rapeseed and soy-based biodiesel to have land-use change emissions – which occur when new or existing cropland is used for biofuel feedstock production – that alone exceed the full lifecycle emissions of fossil diesel. T&E’s analysis adds to these figures the direct emissions of biofuels from ploughing the land, harvesting the crop, adding fertilisers etc., and subtracts emissions from the fossil alternative.

It found that on average, biodiesel from virgin vegetable oil leads to about 80% higher emissions than the fossil diesel they replace, with soy and palm-based biodiesel even two and three times worse. Also, that more than three-quarters of biofuels, including bioethanol and biodiesel, are forecast to have lifecycle GHG emissions similar or higher than fossil petrol and diesel in 2020.

Advanced non-food based biofuels score very well emissions-wise. So why have these biofuels failed to gain any significant market share or attract investment? It’s mostly because EU and member state policy incentives that support first-generation biofuels have created a big hurdle for the truly climate friendly biofuels. For example, EU member states are still able to count the emissions from bad biofuels as zero (0) in their GHG reporting towards the Paris agreement (global level) and the Effort Sharing Decision (EU level). In other words, member states can count the expected 8.4% of biofuels in 2020 as zero-emissions, ie., a net 8.4% reduction compared with oil use.

To give the non-food-based better biofuels a chance, all support given to first-generation biofuels must be cut off. This means reducing the 7% cap to zero post 2020, ending the zero-counting towards GHG emissions for biofuels above the cap (just like they cannot be counted towards renewable energy objectives); and enforcing the ban on state aid post 2020.

Read T&E’s analysis, Globiom: the basis for biofuel policy post-2020, here

For any further information please contact Cristina Mestre, Climate and Biofuels Officer, T&E: cristina.mestre@transportenvironment.org +32 (0)2 851 02 06

Banner photo: Deforestation in Santa Marta, Colombia, to make way for new palm oil plantations © Transport & Environment